How the civil justice system forced Hugh Grant to settle

And why an alternative to that system is difficult to conceive

Hugh Grant has acted in many counter-intuitive scenarios.

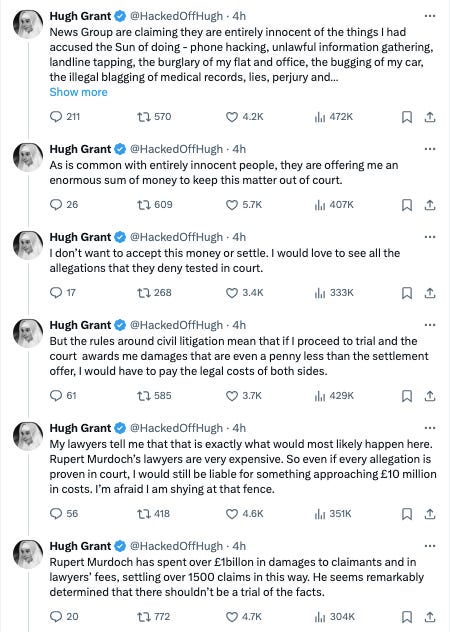

But the situation he described today on Twitter is perhaps the most counter-intuitive predicament of them all:

*

Grant has been correctly advised by his lawyers - both as to the legal position and that he should settle.

Had Grant’s lawyers not given that advice they would have been negligent: this was the legal advice that had to be given.

But it seems wrong - how can this be the position?

And what can be done to change it?

These are good questions - though the second question does not have an easy answer.

*

First let us strip the case of the celebrity of the claimant. We shall the claimant [X].

And we will strip away also the notoriety of the defendant. We can call them [Y].

Now consider the following:

X is suing Y for damages in respect of a tort committed to X by Y.

Damages is a money remedy.

Y offers X more money than X would be likely to win at court if the case does go to trial.

In this circumstance, what should be done?

As the claim is only for money, and more money is offered than the claimant would receive if the case goes to trial, then what is the point of going to trial?

From one perspective, there is no point in the case continuing. After all, X is seeking damages - a money remedy - and X is now receiving money - more money than they are likely to be awarded by a court.

This perspective is the traditional one in English civil litigation: a claim in tort for damages is just another money claim, and so it can be addressed by money.

It does not matter if the tort is negligence, or copyright infringement, or misuse of private information, or whatever. Damages are the thing.

*

But.

For a claimant there may be a desire for a public determination by a court of their claim.

A claimant here can point to, say, the relevant part of Article 6(1) of the European Convention of Human Rights:

“In the determination of his [or her] civil rights and obligations […], everyone is entitled to a fair and public hearing within a reasonable time by an independent and impartial tribunal established by law. Judgment shall be pronounced publicly…”

Surely, X - here, Grant - is entitled to “to a fair and public hearing” with the judgment “pronounced publicly”?

Surely?

*

Well, you would think so.

And in a technical (but somewhat artificial) sense, Grant has not been refused his public hearing and public judgment. There is no express prohibition on him continuing.

What has changed is not his entitlement to a public hearing and to a public judgment - both are still available - but the consequences of him exercising his entitlement.

These consequences are because it is seen as a good thing - generally - for civil cases to settle before trial where possible.

And so the rules of the court are that if one side offers a high amount in settlement then the other side should be, in turn, encouraged to accept that offer.

Such settlements save time and money for the parties and they save scarce resources for the court system.

And as many claimants in money claims are concerned with, well, money then an early offer of money is often welcome.

In general terms: why should X and Y have to go to court if the matter can be resolved before trial?

*

Some offers to settle are flexible, and can be set out in correspondence marked “without prejudice” or “without prejudice save as to costs” (though for many non-lawyers and even some lawyers, these terms can be employed incorrectly and counter-productively).

But the rules of the court have also fashioned a man-trap of a procedural device which we can presume was used in the Grant litigation.

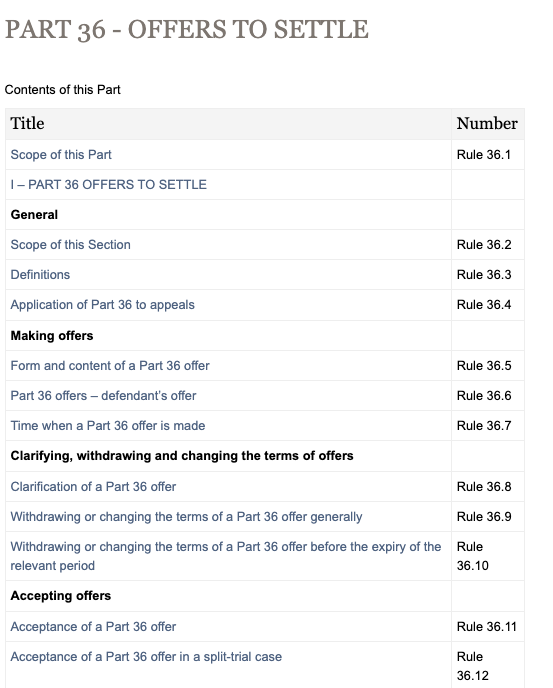

This is the…

(drum roll)

Part 36 is a powerful procedural weapon - for good and for bad - perhaps the most powerful single provision in the civil procedural rules.

Part 36 offers are to be taken seriously - very seriously - by both sides.

In essence, Part 36 provides teeth - like a man-trap - to an offer to settle.

*

A Part 36 offer is usually an offer to settle the entire claim.

If it accepted them the the legal costs of the claimant up to the offer are paid.

Hurrah!

But.

If the Part 36 offer is not accepted then the pressure is on the offeree to “beat” the offered amount a trial.

And if the offeree does not “beat” the offered amount, then the effects are much as Grant says in his tweets.

The offeree has to pay the other side’s legal costs, despite winning the case.

And the stressful thing is that the judge who awards the damages will not be shown the Part 36 offer. The judge will not know what the parties know.

*

It is a very brave - or foolish - party who rejects an even-plausible Part 36 offer.

In practice, there is an art and a science to the timing and setting of Part 36 offers. At the right moment and at the right amount, a skilled litigator can bring a civil claim to a speedy halt.

There is also - unsurprisingly - extensive case law about what constitutes a Part 36 offer and what constitutes acceptance, and so on. This case law is because so much depends on the offer being valid.

It is a man-trap in the middle of a mine-field.

If and when to make and accept (or reject) a Part 36 offer is often the single most important decision a party and their lawyers will have to make in any valuable civil case.

*

In the Grant case, it is apparent that the alleged tortfeasor chose now was the best time to set the man-trap.

It would have to have been for a substantial amount - which was higher than the likely amount to be awarded to Grant.

It was an offer he could not refuse.

*

But.

Understanding the purpose of Part 36 - to make parties consider their positions seriously - does not counter the sense that there is something wrong here.

Yes: the Grant claim is a claim for damages.

But it was also a claim for the court to determine whether there had been wrongdoing by the defendant, which is denied.

And now there will not be a judicial determination - and the defendant can continue to maintain its lack of liability.

A Part 36 offer, as a settlement offer, is not an open admission of liability - or of culpability.

You can see why Grant and others are upset.

The defendant has been able, in effect, to again purchase its way out of any admission or a determination of any wrongdoing.

The defendant has adopted a clever and deft litigation strategy - and it is working well, insofar as no admissions or determinations have been made.

Surely this cannot be acceptable?

*

The issue is that Part 36 works well for many relatively mundane cases.

It means the claimant can get a generous offer of money at an early stage of a case, with their legal costs met. It means a defendant has to err on the side of generosity in the amount that is offered.

It means that hard-headed decisions about the litigation have to be made at an early stage, rather than put off for trial.

In essence, what seems wrong in the Grant case is also what goes well for damages cases generally.

*

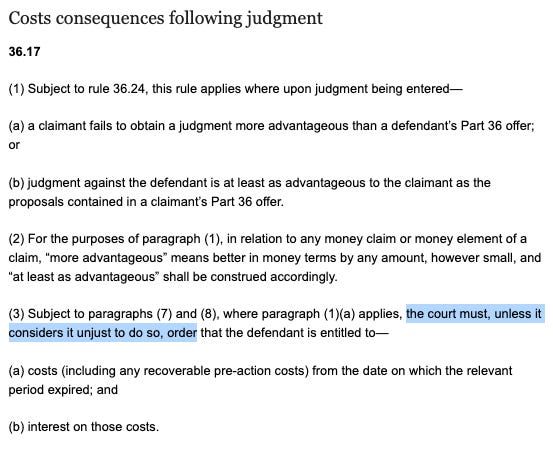

There is an exception to the automatic operation of Part 36 - a court has the discretion not give effect to the consequences of Part 36 if it is “unjust”:

But that is a very high hurdle to meet: and a judge in the Grant case may not be easy to convince that it would be unjust in what is a damages claim for Grant to suffer the consequences of rejecting what was a generous Part 36 offer.

That Grant wanted a public determination of culpability by the defendant would not, by itself, make a Part 36 offer unjust.

*

The hard question is how the system could be changed so that Part 36 could not be used as it has been in the Grant case - but still could be used in other damages claims.

And there may not be an easy answer.

Perhaps there can be a public interest exception - where a certified claim will not meet the normal consequences of not beating a Part 36 offer.

Or perhaps the “unjust” exception could be widened to have regard to the wider public interest.

Whatever the solution - if there is a solution - it would need to not have adverse consequences for those claimants that achieve early resolution of their damages claims against powerful defendants.

*

The ultimate problem, of course, is that this damages claim was doing the work which should have been by other parts of the legal system - and by the aborted part 2 of the Leveson inquiry - where clever and deft use of the civil procedure rules would not help the defendant.

(No doubt lawyers skilled in those alternative procedures would employ their own tactics.)

But this was a damages claim - an important damages claim with wide implications - but still a damages claim. And from a litigation perspective, that is how it has been dealt with, and the claim is now resolved.

Perhaps the upcoming claim of Prince Harry will lead to a determination of wrongdoing.

Perhaps he is the claimant brave - or foolish - enough to reject a generous Part 36 offer.

I saw "X's" original thread, kind of grasped the issues and the unfairness of the advantage deep deep pockets confer, so thanks for providing the legal background to the situation. I note your comment about public interest in a case being pursued. It reminds me of my brother-in-law, a motorcyclist critically injured (life-changing) in a collision with a private bus too big for the country road it was on, pursing an action in negligence. The company's lawyers simply dragged matters out and wore him down. That company went bust, someone else took it over, and started the process again. Stressed at facing a repeat, my b-in-l accepted what was a pittance in damages. This was in Scotland, but I imagine it would be similar in England. The laws around civil procedure really do need an overhaul to rebalance what are essentially asymmetric actions where the tortfeasor has deep pockets.

Was he wrongly advised to sue for damages if that only results in getting money? What would have been the alternative?