Understanding the significance of today's Court of Appeal decision on the Rwanda removals policy

Opponents of the Rwanda removals policy have cause to celebrate, but not too much

Today the Court of Appeal ruled that the United Kingdom government’s controversial Rwanda removals policy was unlawful.

The judgment is here and there is a court-prepared summary here.

By saying the policy was itself unlawful, this means that each and every possible removal of any asylum seeker to Rwanda for their asylum application to be processed is currently unlawful. There are no current circumstances where a removal would be lawful.

The reason for the unlawfulness is that Rwanda is not a safe place for the processing of asylum claims:

This goes beyond the decision of the High Court that each particular removal happened to unlawful, on a case-by-case basis, because an appropriate process had not been followed. The High Court had said that the general policy was lawful, but each application of it so far had been unlawful.

The Court of Appeal now says that even the policy was unlawful. No removal, even with elaborate procedural compliance, would be allowed.

So both in practice and in the round the Rwanda removals policy has been held unlawful.

Opponents of the policy can celebrate - to an extent.

*

Here are some further thoughts about what this decision signifies and does not signify.

*

First, and from a practical perspective, the government’s far bigger problem was the initial High Court judgment. It does not really matter if a policy is (theoretically) lawful if the procedural protections required for each individual case are such that, in practice, removals are onerous and extraordinarily expensive.

I blogged about these practical problems when the High Court handed down its judgment:

Today’s ruling that the policy itself is unlawful makes no real difference to the government’s practical predicament with the policy in individual cases.

And the government appears not to have appealed the adverse parts of the High Court judgment.

The Home Secretary, and her media and political supporters, can pile into judges and lawyers because of today’s appeal judgment. But their more serious problems come from the last judgment, and not this one.

The Home Office is simply not capable or sufficiently resourced to remove many, if any, asylum seekers to Rwanda even if the policy was lawful.

*

Second, the Court of Appeal decision today is likely to be appealed to the Supreme Court.

And, from an initial skim read of the relevant parts of the judgment, one would not be surprised if the Supreme Court reverses this Court of of Appeal decision.

Today’s Court of Appeal decision is not unanimous - the Lord Chief Justice was in the minority on the key question of whether Rwanda was a safe country for processing asylum claims.

The Supreme Court is (currently) sceptical of “policy” type legal challenges, and is likely thereby to defer to the Home Secretary’s view that Rwanda was a safe country for processing asylum claims - a view also shared by the two judges at the High Court and the Lord Chief Justice.

If the Home Office appeals to the Supreme Court then one suspects it is likely to win.

(Though it must be tempting to the Home Secretary to now abandon this - flawed - policy, and blame the judges.)

*

Third, any appeal to the Supreme Court will take time. As it has taken until June 2023 for an appeal decision for a December 2022 High Court decision, it may be another six months before there is a Supreme Court hearing and decision.

And in that time, and unless a competent court decides otherwise, all removals will be unlawful as a matter of policy.

If the government wins at the Supreme Court then there would presumably be further delays while individual challenge-proof removal decisions are made.

In other words, the period for any actual removals before a general election next year will be short.

Even with a Supreme Court win, it will be that few if any asylum seekers are removed to Rwanda before a likely change of government.

(Though it cannot be readily assumed that an incoming government will change the policy.)

*

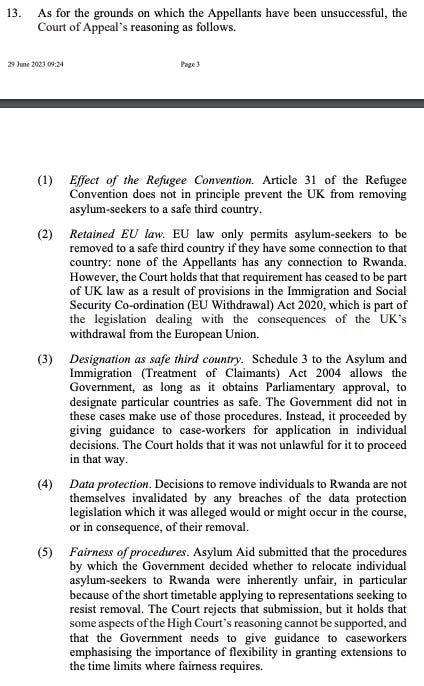

Fourth, it should not be overlooked by opponents of the Rwanda removals policy that the appeal lost today unanimously and comprehensively on every other ground:

These defeats are not any cause for opponents of the policy to celebrate.

*

Finally, there is a possibility of a work-around, which the government could adopt.

In the Abu Qatada case it was held by the courts that a deportation to Jordan for a trial was unlawful because of the use of evidence extracted by torture in the Jordanian legal system.

And so the United Kingdom government did a deal that the Jordanian legal system changed its ways so that the deportation could take place.

Abu Qatada was then, lawfully, deported.

(And then acquitted by the Jordanian court in the absence of such evidence.)

This deportation was presented by the United Kingdom government as a win against pesky human rights lawyers - when in fact the government had in reality complied with the judgment.

Similarly, the United Kingdom government may work with the Rwanda government to improve the asylum system, and correct the evidenced defects, so that concerns of the majority of the Court of Appeal are addressed.

No doubt the government would then similarly present any Rwanda removals on this basis as a win against pesky human rights lawyers - but again it would be the government complying with what the court would have approved.

*

The judgment released today is long - and nobody commenting on the judgment today - politician or pundit - can have read it and properly digested it.

This post is thereby based only on initial thoughts and impressions.

That said, there is reason today for opponents of the Rwanda removals policy to celebrate.

But perhaps not too much.

This is a very useful and rapid assessment

Belated thanks for hugely helpful and speedy analysis