The US Supreme Court judgment on injunctions - what Justice Barrett said

On a curiously unconvincing exercise in judicial reasoning

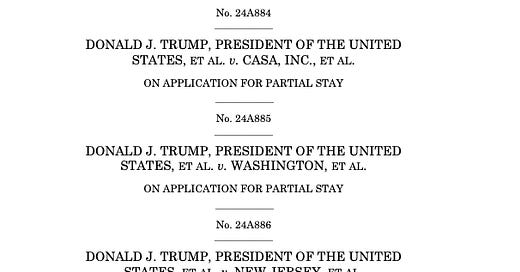

This week this blog is looking at the United States Supreme Court case of Trump vs Casa. You can read the judgment here.

This is the judgment where the court held by a majority that federal courts could not grant “universal” injunctions against the federal government, but instead could only grant injunctions as between the parties to that particular law suit.

The main reason for this case warranting a good hard look is that, on the face of it, the judgment is highly significant.

As this blog averred yesterday, it seems that while onlookers were (mis-)directed into worrying about what would happen if the Trump administration ignored court orders, the conservative majority on the US Supreme Court, with more subtlety and artistry, has now robbed federal judges from making many of the most unwelcome court orders in first place.

This sequence of blogposts is an exercise in testing whether this adverse impression is correct.

*

United States Supreme Court judgments are structured in a particular way. This one has first a syllabus, effectively a summary of the decision of the court and a record of the court’s decision.

Next, on pages 7 to 32 of the pdf, is the Opinion of the (majority of the) court as given by Justice Barrett. It is with this Opinion that this blogpost is concerned.

Barrett is one of more junior members of the court and is the most junior on the conservative side of the court. From time to time she shows flashes of independent thinking, though that independent thinking often still leads to conservative conclusions. That said, it is often worth while reading her opinions, as opposed to those of some of her colleagues.

But this is not one of her more impressive judgments.

*

Here we can quickly go from the United States of the 2020s to the English courts of the 1960s, and in particular to the hallowed and seminal 1963 case of Ridge v Baldwin.

In that judgment, which is one of the founding cases of modern English administrative law (that is the special area of law dealing with public administration), Lord Reid said:

“We do not have a developed system of administrative law - perhaps because until fairly recently we did not need it.”

In other words: there had been changes in the role and configuration of the state - and the courts now had to keep up, and so develop both the substantive law and the remedies available to the court.

(To adapt Philip Larkin: English administrative law began in 1963, between the end of the Chatterley ban and the Beatles' first LP.)

*

Now if we go back the the Barrett opinion, we read her setting out the increase in universal injunctions granted by federal courts against the federal administration (references and citations removed):

“[…] universal injunctions were not a feature of federal court litigation until sometime in the 20th century. […] The D. C. Circuit issued what some regard as the first universal injunction in 1963. […] Yet such injunctions remained rare until the turn of the 21st century, when their use gradually accelerated. […] One study identified approximately 127 universal injunctions issued between 1963 and 2023. […] Ninety-six of them—over three quarters—were issued during the administrations of President George W. Bush, President Obama, President Trump, and President Biden. […] The bottom line? The universal injunction was conspicuously nonexistent for most of our Nation’s history.”

*

Now, why would this be the case?

Why would the growth of such injunctions have accelerated in recent years?

Why, as Barrett states in another part of her Opinion, would it be that “[d]uring the first 100 days of the second Trump administration, [federal] district courts issued approximately 25 universal injunctions”?

If you read only Barrett’s Opinion, you would think that this increase of the use of such remedies against public bodies was solely because of the courts.

But courts do not exist in a vacuum.

Following Lord Reid in Ridge v Baldwin, one explanation is that perhaps until recently the federal courts did not need to use such injunctions.

The increasing use of executive orders under Trump to do thing for which he has no legal basis - including in respect of matters which are really for Congress or other agencies - is left unremarked.

To adapt an economics phrase, Barrett looks at the use of such injunctions entirely as a “supply side” issue.

For her, the courts have gone off on a frolic of their own and developed this jurisdiction to grant such injunctions.

By ignoring this context of the changing nature of the state, Barrett shows that whatever she is as a judge, she is no Lord Reid.

*

Of course, this context by itself would not give the courts a jurisdiction that they would not otherwise have.

But by ignoring this context Barrett provides a one-sided and misleading view of why these injunctions have been applied for and why they have been granted.

And the reason context here is especially important is because we are dealing with what lawyers call “equity”. Equity is, in general terms, about the courts ensuring things are done which should be done.

There are a number of equitable remedies, but the most famous of which is the injunction: an order of a court to stop someone doing something until further order of the court. Injunctions can be permanent, but they also can be on an interim basis - to “hold the ring” so to speak.

And courts develop equitable remedies over time. In England for example, the courts have developed all sorts of orders so as to ensure things are done which should be done - for example here, here, and recently by the United Kingdom Supreme Court with “contra mundum” injunctions against persons unknown.

As the United Kingdom Supreme Court set out in that last decision:

“the court will be guided by principles of justice and equity and, in particular:

(a) that equity provides a remedy where the others available under the law are inadequate to vindicate or protect the rights in issue;

(b) That equity looks to the substance rather than to the form;

(c) That equity takes an essentially flexible approach to the formulation of a remedy; and

(d) That equity has not been constrained by hard rules or procedure in fashioning a remedy to suit new circumstances.

These principles may be discerned in action in the remarkable development of the injunction as a remedy during the last 50 years.”

*

But instead of setting out the development of universal injunctions in the United States, Barrett insists that there should have been no development at all.

Although she mentions the need for equity to be flexible, Barrett says that flexibility has to be exercised within inflexible limits:

“Though flexible, this equitable authority is not freewheeling. We have held that the statutory grant encompasses only those sorts of equitable remedies “traditionally accorded by courts of equity” at our country’s inception.”

And:

“The issue before us is one of remedy: whether, under the Judiciary Act of 1789, federal courts have equitable authority to issue universal injunctions.”

*

This reads both strangely and unconvincingly. Even without reading the dissent, the Opinion of Barrett is not compelling.

Sometimes you can read one judge and then only after reading another judge can you work out who has the stronger position. Even conservative judges can make out a convincing position: that is the nature of judicial rhetoric.

But here you have a weak judgment on its own terms, which ignores both context and the nature of equity.

And given the United Supreme Court has not previously ruled against such injunctions even though the remedies have been around since about 1963, such a ruling needed not a weak judgment but a strong one - both for looking back and looking forward.

Looking back: there have been, according to Barrett quoting a study, 127 universal injunctions since 1963 - and the import of this judgment is that each and every one of those would seem to have been outwith the jurisdiction of the federal court. That is a big step.

(Universal injunctions seemingly also began in 1963, between the end of the Chatterley ban and the Beatles' first LP.)

Looking forward: federal courts now have been robbed it seems of the most effective remedy in dealing with presidential Executive Orders that are outwith any legal or constitutional basis. That also is a big step.

And so this required a similarly big judgment, not this little one.

*

These, however, are initial views on an important judgment. It may be that a more considered view will reveal nuances and meanings that were not obvious on first readings.

But even a more developed view will not generate within the majority Opinion context which is not there, and nor will it remove the inflexibility of insisting equity cannot have significantly developed since 1789.

*

The last word should perhaps go to Barrett, and here you can form your own views:

“No one disputes that the Executive has a duty to follow the law. But the Judiciary does not have unbridled authority to enforce this obligation—in fact, sometimes the law prohibits the Judiciary from doing so.”

*

The last word there being the “But”.

*

Next in this series of posts I will look at the dissents in this case.

As I continue these posts, please become a paying subscriber to this blog so that I can justify spending hours reading and considering such judgments so as to explain them to the public.

Gotta love a Larkin jest! 👊

Barrett's opinion feels rather like Scalia's interpretation of the US Constitution as "dead, dead, dead" applied to the Judiciary Act