The three elements of the Rwanda judgment that show how the United Kingdom government is now boxed in

The Supreme Court decision means that the Rwanda scheme cannot be saved by legislation and treaties alone

This post is about three elements of the judgment of the Supreme Court on the Rwanda policy.

These three parts indicate the difficulties for the government if they seek to use legislation so as to circumvent the judgment.

And two of these parts are about things which the Supreme Court did not decide.

*

The first of these is about, of course, the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR).

Here it should be noted that the court had granted permission for the Convention to be raised as a ground of cross-appeal:

(The government appealed - as they lost at the Court of Appeal - but some of the asylum seekers cross-appealed on points on which they had lost.)

The Supreme Court dutifully set out the Convention point in two paragraphs of the judgment:

You will see, however, that even in these paragraphs the court is careful to set out the Convention position alongside other applicable laws.

The court then makes this point about other applicable laws explicit:

In essence, the court is stating that the ECHR point does not stand alone.

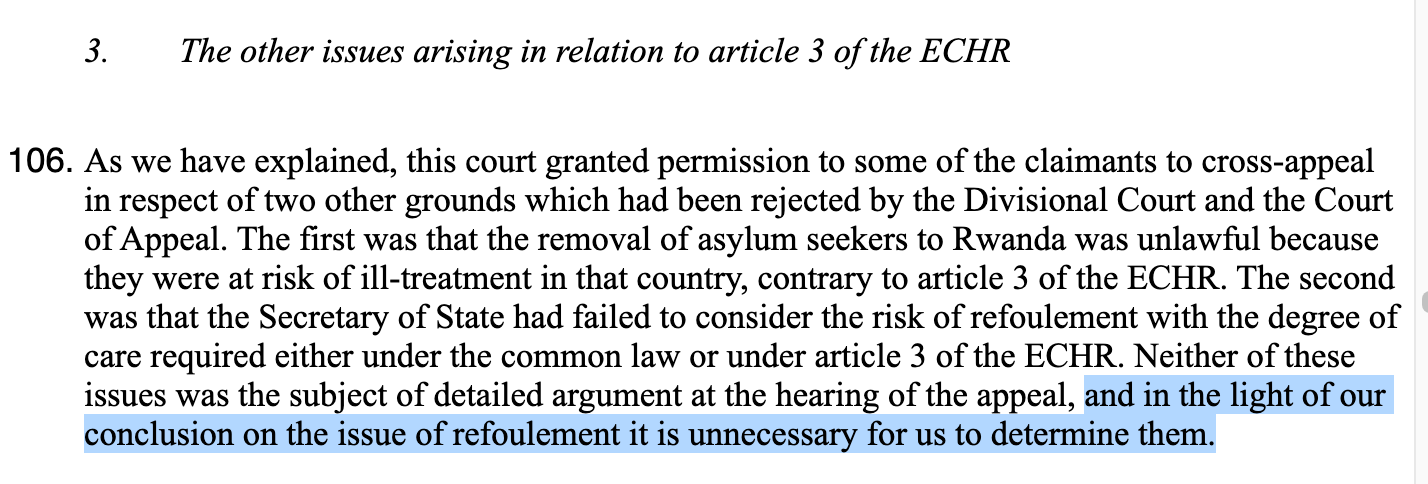

And then in paragraph 106, towards the end of the judgment, the court says (with emphasis added):

This means that even if the ECHR did not apply directly, and even if the Human Rights Act did not exist, then the court would have decided the case the same way anyway, because the key legal principle is in other other applicable law.

That key legal principle is non-refoulement - that is the legal rule that requires that refugees are not returned to a country where their life or freedom would be threatened on account of their race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion. The court found on the evidence before it that there was such a risk if the asylum-seekers were removed to Rwanda.

It thereby follows that if the government were to bring forward legislation to limit the effect of the Convention in Rwanda removal cases it would not make any difference. The courts would just rely on other laws for the same point.

*

And this brings us to the second part, which is rather fascinating.

This is the thought-provoking - indeed, provocative - paragraph 25:

Now this is quite the passage.

So-called “customary international law” is, almost by defintion, outside the power of any one nation state to change. It will apply anyway. As the court says:

“the significance of non-refoulment being a principle of customary international law is that it is consequently binding upon all states in international law, regardless of whether they are party to any treaties which give it effect.”

A nation state may break that law, but they cannot unilaterally change it.

In other words there is no legislation whatsoever the government can bring forward that will mean that this rule would not apply to the United Kingdom.

Deftly, the court ends this point with “as we have not been addressed on this matter, we do not rely on it in our reasoning”.

This suggests that if the Rwanda policy is re-litigated to the Supreme Court, even if the government somehow excludes all the applicable legal instruments (and not just the ECHR and Human Rights Act) then the court may well still hold that the policy is unlawful, on the basis of customary international law.

That is quite the marker.

*

The third part is about what the court did decide.

Here paragraph 105 is worth a very close look:

Here the court is stating that mere formal changes - such as placing the Rwanda policy on the basis of a treaty, as opposed to a flimsy MoU with no legal effect - will not, by themselves, render the policy lawful.

A treaty - which would provide for enforceable rights for individuals - would be necessary, but it would not be sufficient.

The real change required is that there be compelling evidence that, in practice, the Rwanda scheme will “produce accurate and fair decisions”.

And this is also outside of the scope of what the government can push through parliament: for no mere Act of Parliament can by itself change the situation on the ground in Rwanda.

Either the Rwanda scheme can be shown to produce the results required by the applicable laws - and, if need be, customary international law - or it cannot.

And if it cannot, it would seem that the Supreme Court will again hold the policy to be unlawful, whatever legislation is passed at Westminster.

This case now comes down to evidence, not law.

*

Without relying on the ECHR the Supreme Court has placed the government in a rather difficult situation if the Rwanda scheme is to continue.

It would seem that only actual improvements in practical policy can now save the scheme - not clever-clever “notwithstanding” legislation.

And for a Supreme Court that had developed a reputation for being deferent to the executive and legislature on “policy” matters, this is a remarkable position.

Thanks very much for this David. I'll still stuck on the question on what the courts can *practically* do if Parliament passes primary legislation that they consider unlawful. I know they can make a declaration of incompatibility, but that doesn't stop Parliament acting as it is still soverign.

Thank you for, as always, a brilliantly lucid and succinct post on the incredibly emotive also complex legal and evidentiary issues.