The constitutional significance of what happened to the Prime Minister last week

Members of parliament moved for a parliamentary committee to decide what is prejudicial to national security instead of the government

*

Hurrah: now the King's Evil Counsellor is deposed we shall be govern'd well.

*

This is not really a political blog (or ‘newsletter’ as these things are now to be called), at least not in the sense of party politics.

That [A] resigns or [B] loses support is often not of wider constitutional significance.

Not every political drama has constitutional significance.

But.

*

What happened last week in parliament in respect of the Prime Minister and the disclosure of documents relating to his appointment of Lord Mandelson as Ambassador to the United States was constitutionally significant.

As I set out on Friday over at Prospect, the usual position is that everyone in our polity defers (or should defer) to the Prime Minister in respect of national security.

All a Prime Minister normally needs to do is utter this magic phrase, and the House of Commons hushes and High Court judges roll over. Even newspapers can go quiet.

The Prime Minister is normally seen as having special knowledge of, and a special insight into, what constitutes a matter of national security.

*

Last week, however, the Prime Minister Keir Starmer tried to use this magic phrase - and it did not work.

He told members of parliament that the documents relating to the appointment of Mandelson would be released by the government, apart from those which the cabinet secretary deemed would prejudice national security and international relations.

He expected (perhaps) for members of parliament to nod along.

But…

…they did not.

He even resorted to saying that any mistrust amounted to an attack on the integrity of the cabinet secretary.

But members of parliament did not buy this desperate line.

The supposed magic words had been uttered, but there was no magic effect.

Members of parliament did not believe him.

Instead of casting a spell, there was a spell that had been broken.

*

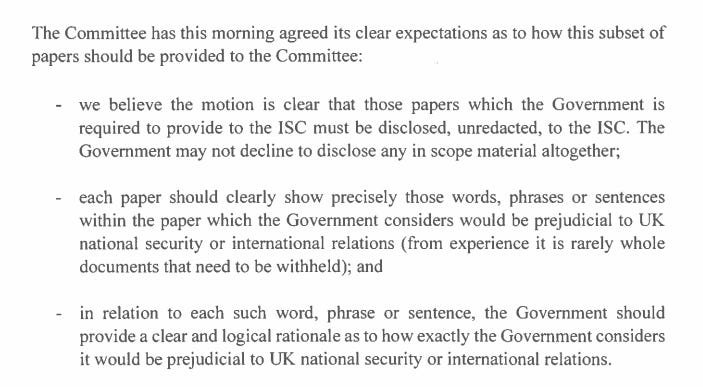

Members of parliament instead swiftly moved to make it that any decision to withhold materials on the basis of prejudice national security and international relations would be made by the Intelligence and Security Committee of Parliament (ISC).

The ISC is not a parliamentary committee in the same way as more familiar select committees, standing committees and all-party committees - it is a statutory creature and has a special legal nature.

But it is a parliamentary committee in the sense that it is a committee of parliamentarians.

And for members of parliament to insist that it is for a parliamentary committee, and not the cabinet, to decide on what constitutes prejudice to national security is an extraordinary development.

The government has effectively lost the confidence of the house of commons on a matter of national security.

Of course, there has not been a formal vote of confidence - but losing such a vote and losing the confidence of the house of commons are not the same thing.

For a prime minister to have lost the confidence of the house of commons means that it is (or should be) only a matter of time before he or she ceases to be prime minister.

And this is especially so for a prime minister who often boasts of his national security credentials as a former chief prosecutor of terrorists and so on.

*

This significant development came about because the prime minister and the government were in a position of extreme political weakness.

This weakness was partly because of the functioning of two mechanisms of parliamentary accountability.

The first was Prime Minister’s Questions - normally irrelevant political theatre - but this time used well by the Leader of the Opposition Kemi Badenoch.

In a line of questions which was impressive both for their precise content and their sequencing, she placed Starmer in the position where he had to expressly admit that he had known at the time of the ambassadorial appointment that Mandelson had continued his relationship with Epstein after the latter’s convictions.

The second was that the opposition - and many government backbenchers - used a “humble address” motion (which if passed obliges the government to disclose documents) for the release of materials relating to the appointment.

The government could see that members of parliament were going to not support the cabinet-knows-best approach to which documents would not be released.

And so in this position of extreme weakness, the government accepted it would be the ISC to decide on what constituted prejudice to national security and international relations and not the government.

Parliamentarians would decided, though ministers would advise.

*

The ISC has now published this (from a constitutional perspective) remarkable letter (which should be read in full).

The letter prescribes the process to be followed by the government in passing documents to the ISC.

It even tells the government that it should not seek to withhold entire documents when only a passage would be prejudicial.

This is heady stuff.

This is a shock to the system where ministers, officials and lawyers will leisurely withhold entire categories of documents on supposed national security grounds.

*

This should not be underestimated as a constitutional event.

What is normally decided by one organ of the state has passed to another, at least for this matter.

And returning to the world of politics, we have a prime minister and government locked into a documented disclosure exercise which it cannot control.

This is a nightmare for ministers, officials and government lawyers.

Of course, a lot of this is down to the politics of the moment - the Prime Minister has long been in a weakening position and those opposed to him (inside and outside his party) exploited a particular moment of extreme weakness.

But it is also down to the functioning of two constitutional mechanisms of accountability - PMQs and humble addresses.

And what is now a nightmare for ministers, officials and government lawyers, is a sign of a functioning constitution.

(Though, of course, the appointment of Mandelson in the first place was perhaps a sign of constitutional as well as political dysfunction.)