On the recognition of Palestine

A close look at an unconvincing letter from "distinguished" UK lawyers

Back in 1990, the late academic authority on legal statehood James Crawford wrote:

“It seems to be difficult for international lawyers to write in an impartial and balanced way about the Palestine issue. Most of the literature, some of it by respected figures, is violently partisan. It is true that this only reflects much of the political and personal debate about Palestine. Still, such a level of partisanship in legal discourse is disturbing.”

Thirty-five years later it still a subject beset by partisanship.

*

A couple of weeks ago a letter was put together in response to the possibility that the United Kingdom may recoginse Palestine. It was signed by some well-known lawyers, some of whom I know and admire.

The authors of the letter were called “distinguished” by various media sources.

*

The published letter was addressed to the Attorney General, and it said:

“In relation to the announcement that the Prime Minister intends to recognise Palestine on certain conditions, we call on you to advise him that this would be contrary to international law.

“As you must know, Palestine does not meet the international law criteria for recognition of a state, namely, defined territory, a permanent population, an effective government and the capacity to enter into relations with other states. This is set out in the Montevideo Convention, has become part of customary law and it would be unwise to depart from it at a time when international law is seen as fragile or, indeed, at any time.

“It is clear that there is no certainty over the borders of Palestine. Could the government continue to recognise millions of Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza as “refugees” (and claiming the right of return to Israel) even though the effect of UK recognition would be that they are on their own territory?

“There is no functioning single government, Fatah and Hamas being enemies. The former has failed to hold elections for decades, and the latter is a terrorist organisation, neither of which could enter into relations with other states.

“You are on record as saying that a commitment to international law goes absolutely to the heart of this government and its approach to foreign policy. You have said that a selective, “pick and mix” approach to international law will lead to its disintegration, and that the criteria set out in international law should not be manipulated for reasons of political expedience.

“Accordingly we expect you to demonstrate this commitment by explaining to the public and to the government that recognition of Palestine would be contrary to the principles governing recognition of states in international law. We look forward to your response.”

*

What is striking about this letter is just how weak it is as a piece of legal reasoning.

If you are partisan - either pro-Israel or pro-Palestine - you may overlook the letter’s merits or de-merits, and you can decide it is a good or bad letter because you either support recognition of Palestine or you do not.

This is the very partisanship to which Crawford was referring in the quote at the head of this post.

But for the rest of us, seeking to make sense of a difficult issue at a dangerous time, we do not need to just cheer or jeer as partisans.

We can look at the merits and the substance of a case instead.

*

Over at Prospect I have set out a brief post about this letter, but on my own blog - where I have more space and can use a more discursive style, I would like to show why this letter is weak stuff - even if it is a very carefully worded letter.

(Below I will quote parts of the letter, and in each quotation the emphasis is added.)

*

First, let us look at a couple of fillers:

“As you must know, Palestine does not meet the international law criteria for recognition of a state […]”

“It is clear that […]”

These are the sort of things lawyers say when they have not got anything stronger. As such they are indications - no more - that we need to be on our guard.

If the authors of the letter were confident they would not need to rely on such stock phrases - and if you read the letter without these fillers it would actually be stronger.

(Indeed the letter does not read like a final draft.)

*

Now let us move to content.

What does the letter say - and what does it not say?

The letter is very careful to use the phrase “contrary to international law”:

“[…] we call on you to advise him that this would be contrary to international law.

“[…]

“Accordingly we expect you to demonstrate this commitment by explaining to the public and to the government that recognition of Palestine would be contrary to the principles governing recognition of states in international law. We look forward to your response.”

To those less used to reading the glorious prose of lawyers, this may seem that the authors are saying that the United Kingdom is breaching international law - that the United Kingdom is proposing to act unlawfully or even illegally.

(Sick birds aside - ill eagles, ho ho - “unlawful” tends to mean there is not a lawful basis for a thing, and “illegal” tends to mean that a thing is in breach of a rule or obligation.)

But the letter does not say the United Kingdom is proposing to act unlawfully or illegally.

The authors of the letter could have said this had they wanted to do, but they chose not to do so.

The letter does give the impression that the authors are saying that the United Kingdom would be in breach of international law - and that is certainly how it was reported:

But again, the letter does not say this.

(One can only hope this misleading impression was not deliberate.)

*

What the letter does say is that a proposed recognition would be “contrary to international law” and “contrary to the principles governing recognition of states in international law”.

The second quotation here is telling: the authors of the letter do not even cite any rule or obligation of which the United Kingdom would be in breach if it were to recognise Palestine.

And the reason they do not do so, as Professor Marko Milanovic avers, in this short but devastating refutal (and not merely a rebuttal) of the published letter, is because there is no rule or obligation of which the United Kingdom would be in breach if it were to recognise Palestine.

(One of the authors of the published letter took Milanovic to task on this refutal, but as Milanovic replies in a comment “the core problem that my post identified with your letter – that you labelled the UK’s future recognition of Palestine as being ‘contrary to international law.’ This created the impression – that was the gist of the whole letter, and that’s how it was portrayed in the media – that the UK would be acting illegally if it recognized Palestine. The basic argument of my post is that there would be no such illegality, and I don’t see how you’ve addressed it. In particular, whose rights, exactly, would the UK be breaching by recognizing Palestine?”)

*

So what is the difference between saying the United Kingdom would be breaching international law (which the authors of the published letter were careful not to say) and the United Kingdom acting “contrary to the principles governing recognition of states in international law” (which the authors of the letter did say) ?

Are these angels malarking on a pinhead?

Is it a distinction without a difference?

*

Well.

There is certainly enough of a distinction to deter the authors of the published letter from saying that the United Kingdom would be acting unlawfully or illegally.

And here we need to look at what the authors of the published letter are emphasising.

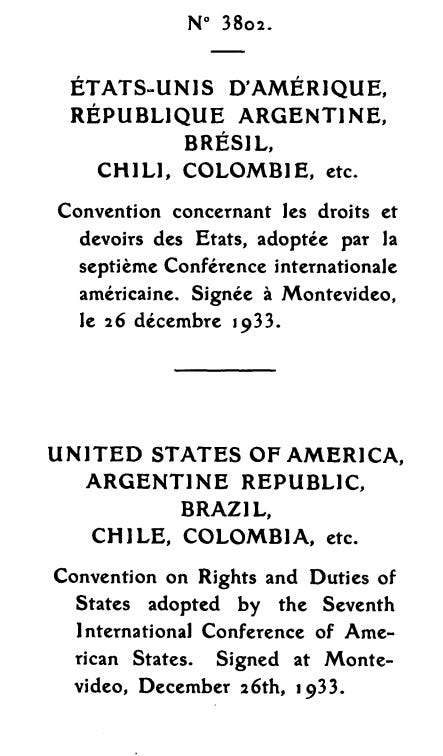

For them, the Montevideo Convention is central. They do not provide a date - it was signed in 1933 - nor do they state that the United Kingdom was not a signatory to the instrument.

It was an agreement of states in the Americas:

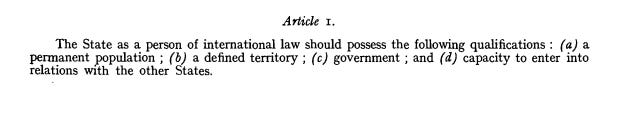

Article I of the English version of the convention provides:

“The State as a person of international law should possess the following qualifications : (a) a permanent population ; (b) a defined territory ; (c) government ; and (d) capacity to enter into relations with the other States.”

These are certainly four criteria for what would constitute a state - and, to borrow a word from the provision itself, they should be four things that a state *should* have, if it is allowed to do so.

But this is not an exhaustive list: there are other qualifications and features of a state, such as there being (a right to) self-determination.

And nor is it a explicitly a compulsory list: there is nothing in the Montevideo Convention which expressly binds non-parties.

Yet it is a list and a useful one - and it was adapted and used, for example, by the Badinter committee dealing with the question of states from the former Yugoslavia.

It is handy list of possible criteria which states may use when recognising other states.

*

But that these are criteria in a 1933 convention which have been usefully applied elsewhere does not mean that they bind the United Kingdom in 2025.

At its highest it means that these are recognised as general principles that may apply - and if you read the published letter carefully, that is all the letter actually says: “principles governing recognition of states in international law”.

The word “principles” here is well-chosen. The authors of the published letter could have said here “rules” or “obligations”.

But they did not, because they could not.

*

In essence, there is no rule or obligation of which the United Kingdom would be in breach if it were to recognise Palestine.

And this is not a surprise.

The recognition of a polity is, literally, a political question.

If the United Kingdom wants to recognise Palestine then it is not breaking any legal rule or obligation.

*

Had the published letter merely told the Attorney General that in any recognition of Palestine by the United Kingdom, regard should be had to the Montevideo criteria of 1933, then nobody could have really objected.

But the letter then asserts that not only that these principles can apply, but their application can only mean that Palestine cannot be recognised.

Here the authors of the published letter go one or two steps too far.

There is, for example, no judicial determination or even advisory opinion they can rely on for that proposition. They have - in simple terms - no authority. It is a bare assertion.

As Milanovic notes:

“It can reasonably be argued that Palestine does not meet the Montevideo criteria, and that it does not currently exist as a state. But it can also reasonably be argued otherwise. This is not an obvious issue – this is why, for example, both the ICC and the ICJ have (so far) avoided pronouncing on Palestine’s statehood under general international law, one way or the other. Yet it is crystal clear that the Palestinian people have the right to establish their own state, by virtue of their right to self-determination, which has twice been authoritatively reaffirmed by the ICJ. Curiously, this is a right that the letter authors do not even mention.”

*

Here there are three possible positions:

the Montevideo criteria can apply to whether Palestine should be recognised as a state;

the Montevideo criteria do apply, and no other criteria;

the Montevideo criteria when applied mean that Palestine cannot be recognised as a state.

The published letter deftly uses the first (undeniable) position and makes it seem, by careful drafting, that it extends to the second and third positions.

It is a clever piece of legal writing: but it does not say what it seems to say.

*

Stepping into the real world from the land of legal writing, over 140 countries have recognised Palestine as a state.

That is about three-quarters of the United Nations.

On a quick count, almost all of the states that actually signed the Montevideo Convention of 1933 - those formally bound by that definition of a state - recognise Palestine.

But according to the authors of the published letter, each and every one of these 140-or-so countries, the vast majority of states in the world, acted contrary to the principles of international law in recognising Palestine.

That is an extraordinary proposition.

**

Nothing in the post above was written on a partisan basis.

My own liberal view is that a two-state approach, respecting the existence of both Israel and Palestine to exist, is the most likely way to address if not resolve the current dire situation.

And as I set out in Prospect, an equally unconvincing letter could be published the other way on this issue.

The intended import of the post above is instead twofold.

First, one should be wary of statements of law that rely on how “distinguished” the author/authors is/are. One of the great things about law is that it is curiously egalitarian - like many sciences and also computer coding - and so it does not really matter how eminent the pundit, it always comes down to substance.

(As a general rule, the more reliance which is placed on how “distinguished” a lawyer is making a point, the weaker the legal point being made.)

And second, one should also be wary of the trend for statements of law by lawyers to be used for publicity and campaigning.

The published letter was not an opinion or an advice for a client, and it was not a pleading or other submission for a court.

*

And finally: nothing in the post above is an endorsement of the position of the United Kingdom.

The position of the United Kingdom on recognition of Palestine is confused.

This is the official statement:

“We are determined to protect the viability of the two-state solution, and so we will recognise the state of Palestine in September before UNGA; unless the Israeli government takes substantive steps to end the appalling situation in Gaza and commits to a long term sustainable peace, including through allowing the UN to restart without delay the supply of humanitarian support to the people of Gaza to end starvation, agreeing to a ceasefire, and making clear there will be no annexations in the West Bank.”

There is no logical or conceptual connection between the question about whether Palestine should be recognised and a ceasefire. It is thereby an irrelevant condition.

Either Palestine exists and should be recognised or Palestine does not exist and so cannot be recognised.

Palestine does not suddenly exist just because there is gunfire, and then suddenly not exist when the gunfire has ceased.

If the authors of the published letter put forward an unconvincing argument against recognition of Palestine, the government of the United Kingdom is hardly putting forward what can be called any argument at all.

*****

Please consider becoming a paid supporter of this Substack so that I can continue to publish posts like the one above.

The use of "distinguished" here makes me think of an oft used expression from my Wee Granny (a Scot) "ah. He thinks he's rhe whole cheese, but he's just the smell".