How the criminal justice system deals with a riot

Those involved in a riot - at any level - should not be surprised that their offences are dealt with more harshly than those acts would be dealt with in isolation

Thirteen years ago, I went along to the south London shopping centre expecting to report on a riot. But there was not a riot.

And so in a splendid exercise of journalism, I filed a piece on a riot not taking place.

The original piece even had a photograph from me of a deserted Bromley town centre – perhaps the least dramatic photograph ever published by any news organ, and certainly the only one that has ever been published that has been taken by me.

*

The paragraphs above are adapted from a post I wrote in 2021, ten years after the 2011 riots.

That 2011 post, in turn, was prompted by comments from a former CPS prosecutor who thought that the prosecutions had been too harsh for some of those “caught up” in the 2011 riots:

“We have to treat people differently otherwise the system’s unfair and so there were people who I regret even having anything to do with,” said [Nazir] Afzal. “In a different atmosphere, in a different environment, they would have been diverted from the justice system altogether – given conditional discharges, probation, restorative justice, pay compensation. But they got rolled into everything else because we didn’t have resources.

“I mean 2011 was the beginning of austerity. I was tasked immediately on taking the role to reduce my budget by 25%, which meant I had to release lots of prosecutors, administrative staff. The police were doing the same, police stations were closing. So we just had to work with the limited resources we had and that meant that we were forced to apply the same rules to everybody and less discretion than we would have been able to exercise otherwise.”

In 2021 these seemed good points.

*

Now it is 2024, and there are more August riots.

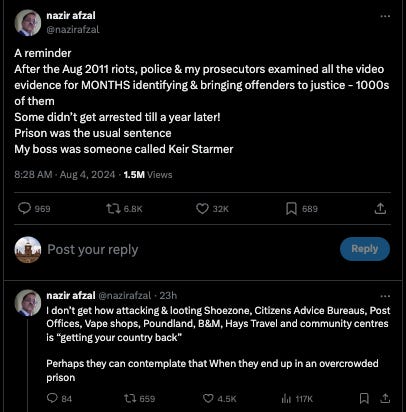

The same former CPS prosecutor quoted above has referred to his 2011 record when commenting on the riots of the weekend just gone:

*

Are the two stances consistent?

Are the regrets stated in 2021 consistent with the pride shown in 2024?

And what is the right way - or the best way - for the criminal justice system to deal with a riot?

*

One way is to treat the various offences in a riot as discrete acts, and to treat them as they would be treated by the criminal justice system if there was no context of wider disorder.

Any criminal damage would be treated as criminal damage would normally be treated, and any arson, ditto.

This would be to treat the rioters as simple criminals, regardless of the wider situation of lawlessness.

There is some merit in that position - and it indicates a justice system unfazed by the supposed “legitimate concerns” of the rioters.

(Of course, if a 'legitimate concern' is a view held regardless of the evidence, and which is used to justify any hateful thing done or said, it is neither a 'concern' nor 'legitimate'. It is an excuse, cloaking something very different.)

In essence, this stance is that the rioters are criminals pure and simple, and so should just be treated as criminals, pure and simple.

*

Another approach is that riots change things - that they change everything.

A riot is, on this view, not a collection of separate criminal acts - each of which could be tried and punished separately.

There is instead an additional quality about the many criminal acts in a riot that means that they should be punished far more harshly than if the criminal acts had been committed in isolation.

This was certainly the approach which the criminal justice system adopted in 2011 (and which the former CPS prosecutor suggested in 2021 may have gone too far in some cases).

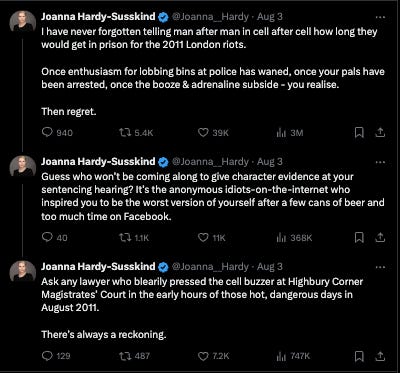

One lawyer who gave advice to those being prosecuted in 2011 has recalled that grim experience:

*

The rioters in parts of England over the last few days will, it seems, be prosecuted as rioters, and not just as individuals doing particular criminal acts.

Few, if any, sensible people will disagree.

This was not normal, everyday criminality.

Indeed, the disturbances of the last few days seemed worse than riots. They appeared to be more like concerted pogroms. They looked as if they were politically directed and coordinated.

In essence: what happened may have been more akin to terrorism - deliberate political violence.

*

SCHULTZ: It is nothing! Children on their way to school! Mischievous children! Nothing more! I assure you! Schoolchildren. Young—full of mischief. You understand?

~ Cabaret

*

There has in the United Kingdom long been a special branch of criminal law that dealt with terrorism offences.

This is because the criminal law also does not treat terrorists as normal criminals, pure and simple.

There is an additional quality to the criminal acts in question which mean a different legal response is required. Indeed, terrorism law has offences where there is no non-terrorism criminal counterpart.

It may well be that those who directed - or at least incited and encouraged - the 2024 rioters from afar will find that they have brought themselves within the scope of various terrorist offences.

*

There is no one way for the criminal legal system to deal with a riot.

But.

Those who get involved in a riot should not be surprised when the legal system treats their offence as being worse than if the criminal act had been done in another context.

And those who incited and encouraged the rioters should also not be surprised if the legal system treats their involvement as being within the context of terrorism.

For, to conclude, section 1 of the Terrorism Act 2000 is in broad terms: